|

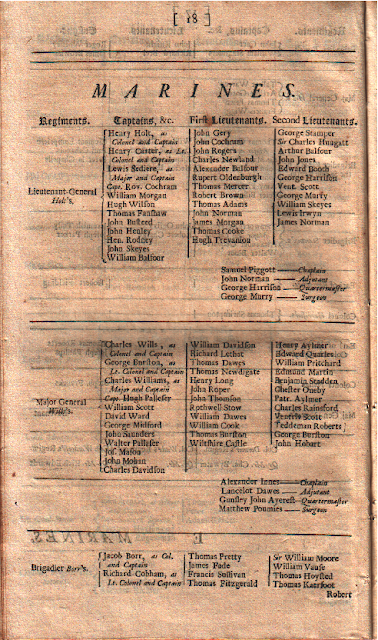

In his book, Dorrell describes the campaigns on the Iberian Peninsula in chronological order. Thus he begins with the Anglo-Dutch raid against Cadiz and Vigo and Portugal's entry into the war and describes each year's campaign right through the evacuation of the region in 1713. Lists of regiments for the various campaigns and battles, and some uniform details, are provided. The book is adorned by over thirty illustrations, and maps are included to show troop movements, etc.

Given the scarcity of books on the Peninsular theatre during the War of the Spanish Succession, this book should be welcomed for providing a neat and concise survey.

There are, however, several aspects of this book that could have been improved or avoided.

1. A first are several remarks on the general layout, typesetting and 'look and feel' of the text:

a) Though highly subjective of course, the book just doesn't look attractive by browsing through it. This is mainly caused the by the lack of indentation where orders of battle are provided, which gives the text a solid and massive appearance. Here using a tabular way of formatting, and avoiding left-alignment, would have helped.

b) Furthermore, it is custom for books (other than novels of course) that new chapters start on an odd (i.e. right-handed) page, even though this may create a blank page preceding the new chapter.

c) Another point of criticism is that the page numbering of the main matter (in Arabic numbers) continues that of the front matter (in Roman). Page numbering usually (re)starts at 1 for the main matter.

d) The painting of the Battle of Almansa is wrongly attributed to Ricardo Balaca, a nineteenth century artist. He indeed made a painting with the battle of Almansa as subject in 1862. The painting reproduced in the book is by Buonaventura Ligli, who made this painting in 1709.

e) The maps are not scaled uniformly, i.e., the map-scale is of course different depending on what is shown, but it is good practise that the text in the maps is in the same format regardless of map scale.

These aspects give the book a somewhat unfinished appearance, and could have been avoided in my opinion.

f) The text reads as if it was compiled sequentially from sources given in the bibliography, without giving it a second thought. This results in a somewhat uneven introduction to general concepts, and the text lacks a certain smoothness. This could have been avoided by putting that kind of details into an introduction or earlier chapter.

Next, there are several aspects of the contents itself that could have been improved. I will address a few:

2. The ``British Army'' was one of main stakeholders, and the first chapter gives a basic introduction (pages 15-17) . Though the author rightly states that there was no ``British Army'' at this period, he seems to have overlooked completely the concept of establishment. Instead of an army, there were three establishments: an English, a Scots and an Irish, one for each of the three kingdoms. Ireland is not mentioned at all in this part. The concept of a ``British Army'', as an institution, was however something for the future. On his discussion of the regimental organisation, the author overlooked the fact there were many more establishments (i.e. authorised organisation and strength) for regiments than he states, and (British) regiments serving in Spain were organised according to several establishments, all depending on where they came from. This is a confusing topic, but the short-cut taken by the author is simply to simplistic. In his discussion of the cavalry (page 17), the troop as building block for regiments and owned by a captain is omitted in favour of the more popular squadron.

3. Dorrell rightfully mentions the Dutch (chapter 3, page 29ff.) as an important stakeholder. According to Dorrell, the Dutch contribution to the Iberian Peninsula was not as large as it could have been. However, Here the author should have been aware that the English and Dutch forces sent to Portugal and Spain, even the complete effort regarding that region, was settled according to quotas: 2/3 English and 1/3 Dutch, giving a more objective and nuanced interpretation of why there were relatively few Dutch troops. Though Dorrell uses some German language sources, it is a pity he didn't consult the Dutch "Het Staatsche Leger".

4. Another important player was Portugal, and the contributions of the Portuguese army have somewhat been neglected in the literature on the War of the Spanish Succession. Here Dorrell mentions that the obscurity of information is in part caused by the custom of naming the regiments after its colonel, whereas other states used a more clearer (e.g. numerical) method of naming. This, however, it not entirely correct. Regiments of other nations were still named after their colonel, or had some other designation when named after, e.g., a member of the Royal family. The concept of precedence added some ordering, but the habit of adding a numerical addition to a regimental title was something of a later date.

5. The capture of Minorca is dealt with very shortly, and unfortunately the details on the invasion force are not according to the latest insights. Furthermore, it is a pity the author omitted the garrison on the island between 1708 and 1713. The same can be said for Gibraltar.

Because of the above remarks the final evaluation of this book is more elaborate than usual.

Given the subject, I would rate the book as recommended and I am convinced it will find its way to the libraries of (amateur) historians and students of the battles of the War of the Spanish Succession

Unfortunately, the book's appearance is not up to standards, and some serious editing would have been useful. Furthermore, though the author is no doubt complete in providing orders of battle and narrating on the many battles and campaigns, and for this achievement the author deserves full credits, there seems to be a lack of completeness and consistency (as in ``big picture'') in his story.

These two points combined give the book the appearance of a manual for those wishing to re-create battles, and those looking for orders of battle. And for that purpose I feel this book will be useful.

However, the book would have benefited from a more out-of-the-box thinking, to get the big picture and conceptual understanding of an early eighteenth-century army more clear.

So I would rate the book as recommended and certainly as very relevant because of the lack of literature on this topic and the amount of work put into it by the author. However, this is with reservations depending on what the reader is looking for.